A Quick History Lesson on How We Have Understood “Christian Mission”

Part 1: Evangelicals and the Shift to Seeing Mission as Purely Evangelism.

A survey of the recent history of evangelical understanding of Christian mission reveals an ebb and flow between seeing the mission of God’s people as being about the redemption of all aspects of life on earth to being solely about evangelism and the destiny of souls in the afterlife.

The Legacy of William Carey

The “father of Protestant missions,” William Carey (1761-1834), focused on the “Great Commission” at the end of the Gospel of Matthew as the purpose of Christian mission.

David J. Bosch states,

“Carey—like thousands of other missionary enthusiasts since—has built his case almost exclusively on the commission of the risen Lord. Christ has commanded us to go into all the world, therefore it is incumbent upon us to go.” (D. J. Bosch, “Hermeneutical Principles in the Biblical Foundation for Mission,” Evangelical Review of Theology 17, no. 4,1993).

The text of the Great Commission is

18 Then Jesus came to them and said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. 19 Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” (Matthew 28:18-20, NIV)

Bosch criticizes Carey and those who follow him with starting with a presumption that…

“…we already know what ‘mission’ is and now have only to discover it in Scripture. For most Western Christians, Roman Catholics and Protestants alike, from the Middle Ages down to our own times, mission meant the actual geographic movement from a Christian locality to a pagan locality for the purpose of winning converts and expanding the Western Church into that area.”

Bosch says that the presumption about mission was…

“defined almost exclusively as the verbal proclamation of an other-worldly message and a preparation for the hereafter. Consequences of mission, such as social and political changes, were, in essence, regarded as by-products. Other activities of the missionary societies, such as education and medical care, were only ancillaries to the verbal proclamation of the gospel.”

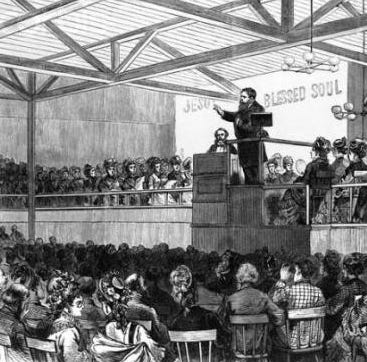

Some evangelists in the United States, such as D. L. Moody (1837-1899), used

“the priority of evangelism, together with premillennialism, as an excuse to avoid saying much on social issues.”

Evangelism vs. Social Action

Historian George Marsden makes the case that for most evangelicals in the middle and end of the nineteenth century,

“the principal emphasis was not on social concerns, but they were certainly an integral part of the evangelical program.” (Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, 2 edition, Oxford University Press, USA, 2006, p. 90).

But at the beginning of the twentieth century, influential Christians like Walter Rauschenbusch and Henry Emerson Fosdick began writing about what would eventually be called “the social gospel,” which defined sin as injustice in society and promoted the belief that the kingdom of God could be ushered in by the Church transforming society.

According to Marsden,

“Until this time in American history considerable numbers of revivalist evangelicals had always been in the forefront of social and political reform efforts (antislavery, for instance), even though many other evangelicals had been socially conservative. In the twentieth century, however, evangelical participation in progressive reforms, except in some of the older crusades such as for prohibition, dwindled sharply. As theological liberals spoke more and more about the social implications of the gospel, revivalist evangelicals spoke of them correspondingly less.” (Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism, Eerdmans, 1991, p. 30).

The Modernist - Fundamentalist Battle

In the early 1900s, “Modernists” (i.e., liberal Protestants) defined the Christian mission as philanthropy and development and began no longer seeing non-Christian religions as false or intrinsically evil.

“Modernists tended to increasingly emphasize mission as democratization and improvement of living standards. Hospitals and schools were no longer seen as means or partners of evangelism, but as ends in themselves.” (Craig Ott and Stephen J. Strauss, Encountering Theology of Mission: Biblical Foundations, Historical Developments, and Contemporary Issues, Encountering Mission edition, Baker Academic, 2010, p. 129).

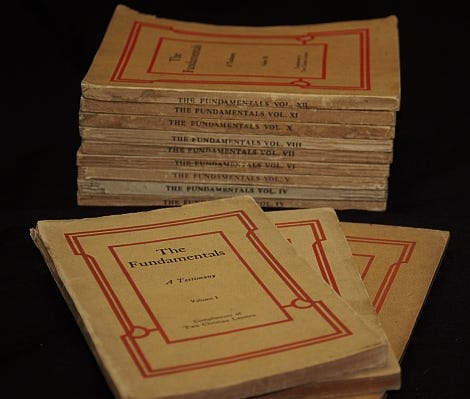

The early twentieth century saw a clash between Christians who emphasized the social gospel and those who were influenced by North American revivalism. In response to the optimistic progressive modernists, conservatives advocated what they called “The Fundamentals,” stimulated by pamphlets of that title funded by Lyman Stewart, a wealthy businessman and proponent of Dispensationalism.

Marsden comments,

“The practical essays and personal testimonies in The Fundamentals display an overwhelming emphasis on soul-saving, personal experience, and individual prayer, with very little attention to specific ethical issues, either personal or social.” (Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture, p. 120).

Ott and Strauss add,

“Evangelicals rejected the social gospel and thus shied away from any social agenda whatsoever for church and mission. The fundamentalist-modernist debate polarized the positions further, impacting mission work and theology.” (Ott and Strauss, Encountering Theology of Mission).

But there came a new generation of evangelical Christians who saw the divorce between evangelism and social action as being unbiblical and unchristian. Next, we’ll look at Carl F. H. Henry and the rise of the Neo-evangelicals in the mid-1900s.